THE KEY TO SUCCESSFUL STRUCTURAL REFORM

A couple of weeks ago I was running a simulation-based training session on performance improvement, and asked the participants to report back on their homework. (I drive my participants hard: they have to do homework between sessions).

In the previous session I’d been talking about the importance of properly defining a problem before attempting to solve it, and using process mapping as a means to do that.

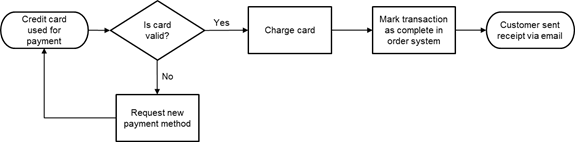

Process mapping is simply where you analyse a process by breaking it down and documenting each step and decision in a flowchart-style visual format. An example of a simple process map for a credit card order is shown below:

One participant reported back that her unit was being merged with two other similar divisions from other organisations as part of a consolidation into a ‘portfolio cluster’. (Attention government readers: sound familiar?)

Inwardly, I braced myself to defend why process mapping and proper problem formulation are nonetheless good ideas, and necessary to performance improvement and functioning, even when there’s structural change.

Structural change is a stumbling block to improving performance, because to improve a process you have to stabilise it, and how can you stabilise a process when the ground keeps shifting because of reorganisations? Structural change is the hobgoblin of performance improvement.

Or so it seemed at that moment.

But the participant went on to talk about how she’d got the players from all three divisions together and they’d collectively mapped their processes. In doing this, they'd created a shared picture of the process at large, and differences between their respective approaches had surfaced. This whole activity, the participant said, had been very useful. It set the scene for structural consolidation.

So, rather than the structural reform being a roadblock on the way to process improvement, the process improvement was a tool to carry out structural reform! Voila!

My response to the participant: “You’ve stepped across the threshold of the Temple of Enlightenment!”

I’ve long known that having a clear business goal is the key (and in my view, the only) reason to carry out structural reform. Fiddling about with organisational forms, chopping and changing divisions and work units, ‘spill and fill’ campaigns and the associated accoutrements (new logos, letterheads… etc.) should be in the service of a crystallised, pre-defined performance objective.

In organisations at large, especially public sector ones, restructures are too often carried out to give the appearance of doing something, or because there’s no other way to carry out wholesale, industrially sensitive staff (and hence budget) cuts. These campaigns, unsurprisingly, generate uncertainty, angst and frustration amongst staff and executives alike.

You can’t help being reminded of the sentiments expressed in the opening pages of Peters and Waterman’s classic In Search of Excellence:

An organisation chart is not a company, nor a new strategy an automatic answer to corporate grief. We all know this, but like as not, when trouble lurks, we call for a new strategy and probably reorganise.

Compare that to my participant’s case: performance and the pathway to client outcomes were centre-stage. In this case, with the addition of some basic data, there’s a clearly visible, mapped basis for changes to the amount, allocation and activity of staff. There will still be pain (there always is with structural reform) but there’s a reason for the pain, and a gain from it which is understood by those involved. That takes a lot of the sting out of it.

I’ve been in and around government long enough (20 years next year) to realise that operational performance and client results alone are hardly the axis on which government turns. It is, rather, agenda-, media- and stakeholder- driven. But I remain steadfastly of the view that there are cogent agendas to be run which improve performance and which at the same time meet the imperatives of stakeholders and the media.

In fact, that for me is the working definition of management, particularly for those in the public and not-for-profit sectors: being able to define and improve performance while enhancing the organisation’s standing with stakeholders, the media, and the public at large. The drive for credibility and plausibility which is at the heart of government doesn’t run counter to improved performance; it can and should be the result of it. That provides a good approximation to true north for any manager or executive.

Just ask my course participant.

Kind regards,

Michael Carman

Director I Michael Carman Consulting

PO Box 686, Petersham NSW 2049 I M: 0414 383 374

© Michael Carman 2013