THREE WAYS TO VACCINATE YOUR ORGANISATION AGAINST AN EPIDEMIC OF MEETINGS

One of the most common complaints I hear is that people suffer an excess of meetings: they can’t get any work done because so much of their day is taken up in a seemingly endless stretch of back-to-back meetings.

And these meetings are (unsurprisingly) not highly enjoyable, life-giving activities. Rather, they are ponderous affairs that meander in and out of relevance, where no decisions are made, and the key issues are resolutely avoided. The meetings are too long, too many actions are pending, and too many of these actions are rolled over from meeting to meeting. Frustrating.

The fact that former GE Chairman and CEO Jack Welch described a similar phenomenon in a recent LinkedIn post suggests the complaints I hear are not isolated instances.

What are we to make of all this?

Management Malaises

I contend that the epidemic of meetings is a symptom of a broader management malaise … in fact three of them.

Firstly, the organisation is unclear about what it is trying to accomplish: in this instance there is no anchor or reference point for meetings when they occur – lack of organisational goals flows through to a lack of focus in meetings. As well, managers and staff try to find purpose and direction by holding meetings.

Secondly, there is insufficient leadership or firmness of purpose, so that the ability to make (and keep) decisions is under-developed. Even when a decision is made in a meeting there isn’t the discipline to keep it: it is often second-guessed or undermined by someone going directly to a senior manager after the meeting has concluded to circumvent the decision. (I find this a particularly noxious behaviour).

And thirdly, there is no follow-up between meetings: in the absence of a structure for accountability, meetings serve as a substitute for action, rather than a means of monitoring and progressing it. The composer Claude Debussy once remarked that music is the space between the notes; in a similar vein, action and results occur in the space between the meetings.

To address such fundamental strategic and cultural factors is a tall order, and one that is unlikely to occur simply because of a mass of meetings.

What to do?

Three Ways to Ease the Pain

Despite the spread of the meetings epidemic, measures can still be taken to inoculate your organisation. Here are three:

1. As simple as it sounds, being clear about the purpose of a meeting before calling it serves as an anchor: what is the meeting supposed to accomplish? Is it designed to inform and update participants, monitor actions, or make a decision?

If you can’t articulate the purpose of the meeting before calling it, then don’t proceed with the meeting.

2. State the purpose at the beginning of the meeting and ensure the meeting addresses itself to that purpose. A quick check before the close-out of the meeting (“Is everyone up to date on the status of the project?” “Have we decided on the process and dates for training new staff?”) will help ensure the actual purpose has been met. Any major issue which emerges during the course of the meeting should be captured and dealt with through a separate process rather than derailing the original goal of the meeting.

3. Prepare and distribute an agenda in advance of the meeting. One piece of research suggests that the best predictor of the success of a meeting may be a written agenda distributed in advance. The agenda should clearly state what the purpose of the meeting is (refer both points above).

Counting the Cost and Trimming the Waste

I have developed a methodology to evaluate meetings and quantify the impact of low or no-value meetings. This helps organisations, particularly professional services firms which use time-based billing, to size up the amount of time and money which can be saved by making meetings worthwhile.

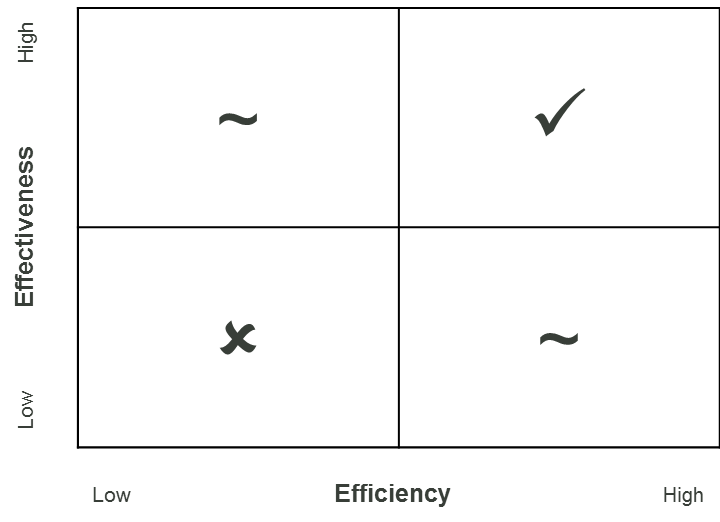

The process starts with a 2 x 2 diagram (below) developed by Alan Weiss which plots participant ratings of a given meeting’s Efficiency (did it start on time? were all the necessary resources on hand? were all the required people present?) and its Effectiveness (did the meeting have a clear purpose? did it accomplish what it was supposed to?).

Each participant keeps track (say, for a week or a fortnight) of what meetings they attend, how long each meeting lasted, and score each meeting’s efficiency and effectiveness. At the end of the period I take this data away, do some number-crunching to pull together each meeting’s scores, duration and attendee’s charge-out rate (or hourly cost) to come up with figures for total hours and dollars wasted.

We then apply strategies for each time-wasting meeting depending on which quadrant it is located in, to recoup losses and start realising the gains from making the time-wasters more worthwhile.

This method has other advantages too: it brings people together to collaboratively decide how to define the effectiveness of meetings, and it enables comparison of each participant’s ratings of the same meeting. Fascinating.

If you think this kind of service would assist your organisation, drop me a line at info@mcarmanconsulting.com or call me on 0414 383 3740414 383 374 … we may just be able to limit the spread of the meetings epidemic.

Regards,

Michael

Director I Michael Carman Consulting

PO Box 686, Petersham NSW 2049 I M: 0414 383 374

References:

Drucker, P. (2002) The Effective Executive HarperCollins.

Romano (Jr), N.C and Nunamaker, J.F., (2001) ‘Meeting Analysis: Findings from Research & Practice’ Proceedings of the 34th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences – 2001 p.10.

Weiss, A. (2006) The Great Big Book of Process Visuals Las Brisas Research Press, pp.56-7.

© Michael Carman 2015