How to Sell a Case for Change: Three Ways to Boost Support for Your Initiative

How do you marshal support for a change initiative?

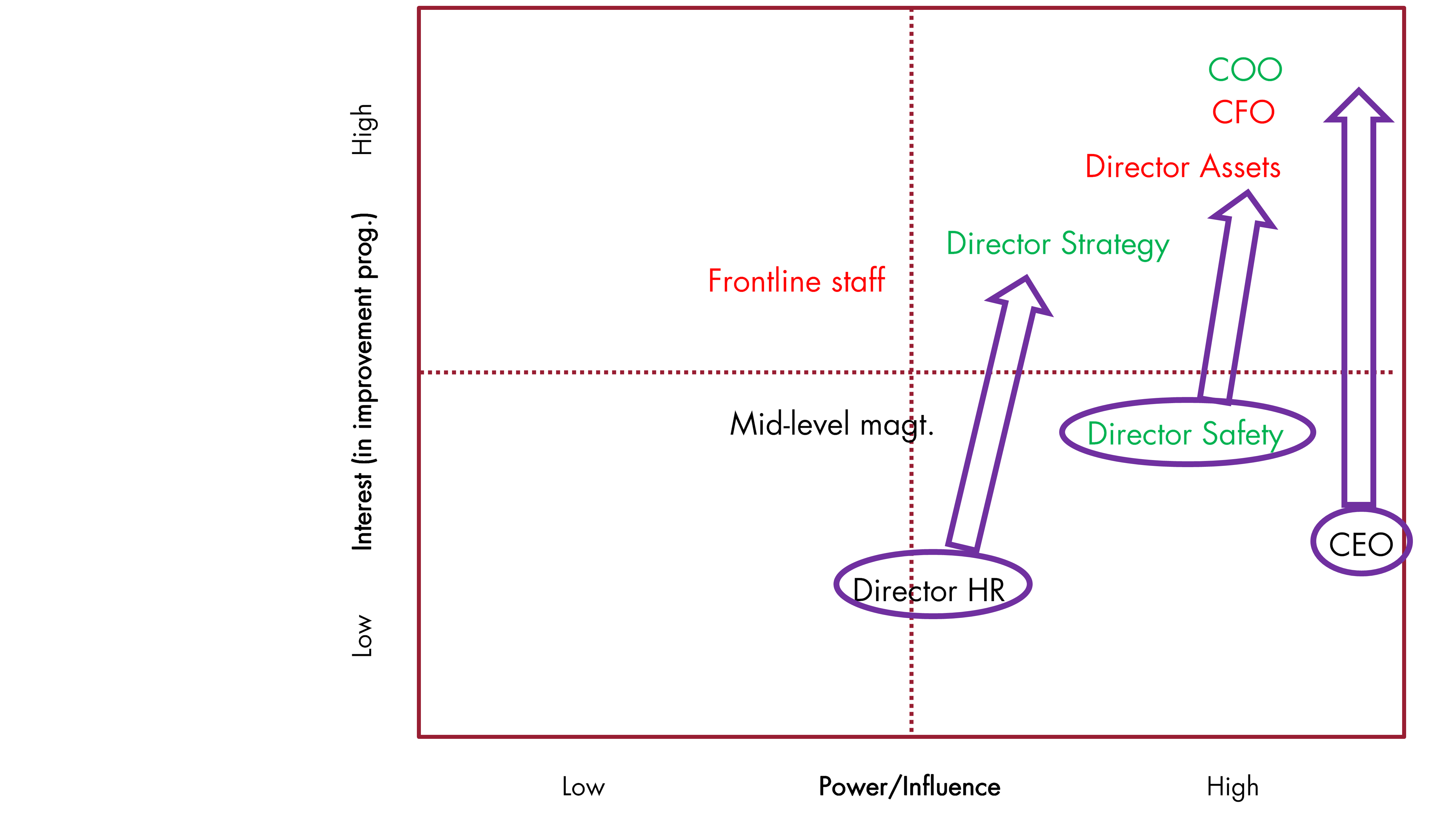

In last month's newsletter we saw how to deal with detractors and malcontents in a change effort. We looked at collaboratively structuring the analysis and planning (ie. plotting and scheming) of stakeholder engagement: how to move the players from where they are to where we need them to be. To do this we used a Power-Interest grid that plots each stakeholder in terms of their influence and their interest (in the political sense of the term – not curiosity) in a particular issue or initiative.

This month, rather than countering resistance, we look at how to garner support for a change initiative.

Because we are taking the positive approach of boosting support rather than dealing with opposition, the imperative as it is expressed in a Power-Interest grid is not about moving detractors out of the upper right-hand high-power – high-interest quadrant, or turning detractors into supporters (turning those colour-coded red to green). Rather, the focus here is on increasing the interest of influential but currently non-engaged stakeholders, and converting the ‘neutrals’ to green. Using our example from last month, this translates to something looking like this:

So … how exactly do we increase these individuals’ interest in our initiative? Here are three ways.

1. Be a Friend with Benefits

Every change initiative should have a well-defined business case which identifies and quantifies the benefits. That’s the logical first reference point for winning people over.

But there are benefits … and then there are benefits. There are benefits in the abstract (such as a five point increase in employee engagement, or an acquired company being properly integrated with the existing business) but then there are ways to make these as real and concrete as possible. There is a credible body of research which suggests it is not the size of the benefits which counts, it is their tangibility. As the authors of Made to Stick say: “You don’t have to promise riches and sex appeal and magnetic personalities. It may be enough to promise reasonable benefits that people can easily imagine themselves enjoying” (emphasis in original).

The challenge therefore, is to take those benefits and then translate them into terms which are easily visualised … even personal. A good way to do this is to ask how the benefits will manifest themselves: how will they be made visible? How will you know they’re there?

An increase in employee engagement will be evident in higher productivity, higher reported morale, a reduction in the number and intensity of conflicts between staff, a lighter ‘mood’ in the workplace, and reduced sick leave and absenteeism. A well-integrated business acquisition will be discernible by a reduced risk of operational outages; every new staff member being inducted within three weeks (say) of go-live; higher reported levels of staff knowledge of facilities and processes; and an absence of payroll and finance glitches for new staff.

Think through the benefits and keep asking What are the benefits? How do they become visible? and Why do this? Cast a wide net with your benefits capture: it’s easier to sift and discard extras later than it is to try and think of new ones on the hop.

2. Go Face-to-Face

I have written previously about how there’s something compelling about being face to face with people which is not present with other forms of communication. This is why politicians, even in the age of Facebook and Twitter, still go out on the hustings.

Some years ago I was undertaking a change project for an organisation which was going through a merger and restructure, and I had to gain the cooperation of an executive in the ‘acquired’ organisation. This person was a well-known recalcitrant whose general intransigence was the stuff of organisational legend: I had a meeting with the person in question, heard him out, incorporated his input and made a couple of minor tweaks to reflect his views. He ‘bought in’ to the process (ie. didn’t kick up a stink) and I was able to complete my assignment to the CEO’s satisfaction without interruption or incident.

This highlighted to me the importance of getting in front of people, giving them a chance to have their say, and ‘drawing out the crabs.’

Every encounter provides the opportunity to add an emotional ‘coating’ to our relationships. The truth of the matter is that irrespective of the logic or rightness of our case, being seen as fair dinkum, a decent person, stacks the deck in favour of our cause. An acknowledging smile, remembering to ask after an ailing family member, listening to a gripe about some facet of work may all seem a bit twee for the serious business of organisational change, but they are the mortar of civility that keep the bricks of corporate life connected. Every real-time encounter provides an opportunity to demonstrate that we are personable, and to layer rapport and civility into our work.

For that reason, I recommend getting in front of people – and making it a generally pleasant experience – as a means of helping sell your initiative.

3. Create a Bandwagon

The ideal scenario for a change initiative is for it to have such momentum that it’s a no-brainer that people would get behind it. This is why senior management support for an initiative is so critical: without it, people will feel free to opt in or opt out. And if they have other things on their plate or seek an easy life, well, they’re not going to opt in…

Peer pressure isn’t only an issue for teen smoking – norms exist in every group. (They’re one of the things that makes a group a group). Normative pressure can be created and marshalled in an executive team. Active championing of a change initiative creates pressure to ‘sign on’, and this has to continue at least to the point where a critical mass of profile and support is reached.

The CEO or senior leader needs to bang the drum for an initiative loudly and constantly, providing plaudits for early followers. Exemplars and models need to be feted. The message should be clear, consistent and cascaded down the line. This is less the implementation of one more program from Corporate than it is the start of a movement. You have to engineer it such that supporting this initiative is the done thing – it’s a no-brainer. Get on the bandwagon or get left behind. This is good peer pressure, the type that rouses an organisation from inertia and gets things moving towards a positive end-point.

Support-Building in Action

And so, to return to our hypothetical case study from last month. Recall that the Chief Operating Officer (COO) aims to introduce a program to drive improvements in processes in order to meet a new international quality standard. The CEO only has passing interest in the initiative at present as he is preoccupied with a range of other issues. The Director Safety is broadly supportive since the initiative will improve her KPIs, but she is not engaged at the moment. The HR Director is basically neutral and has not engaged with the initiative to date.

Using the techniques above, here’s how the COO went about building support for the initiative.

Firstly she sat down with the CEO at her one-to-one meeting and explained the company-wide benefits from driving process improvements that meet the new quality standards. The CEO knew about these in the abstract, but the COO also drew attention to the pervasive lift in the ‘feel’ of the organisation up and down the length of line management. The uplift not only in operational performance but also morale, she explained, would be associated with the CEO and be seen as his legacy. She was forthright about the ask on his time as she requested he speak to regional staff to promote the effort across the organisation. She provided the CEO with the first draft of a set of dot points he could use in talking to staff, so the task was already set and the CEO was primed with minimal extra work on his or his office’s part. (This also gave the COO the opportunity to ‘own’ the framing of the narrative around the effort). She also suggested a series of forums and a possible itinerary for the CEO’s consideration.

The CEO obliged enthusiastically and at the next executive team meeting spoke about the initiative at length and informed all present that support for the effort would be written into their performance agreements and group and divisional business plans. He scheduled a series of talks and forums around the organisation, and video-conferenced with areas that he couldn’t get to in person.

The COO had already had a brief conversation with the Director Safety to re-engage her and start her thinking about how she could use the accreditation to boost measured safety performance (and her own KPIs). When the CEO started talking about the initiative at the executive team meeting, the COO and Director Safety exchanged a knowing glance.

That left the HR Director. He was initially nonplussed about having to change a swathe of position descriptions to reflect the new accreditation. The COO had a meeting with him and tipped him off ahead of the executive team meeting; when the HR Director heard the CEO say that support for the initiative was mandatory and would be part of his performance agreement he knew he had to vocalise support. The COO also provided the salve of giving the HR Director a contact person in her office as a liaison point to assist with the changes to the PDs.

* * *

This is what building support for a change initiative looks like: the structured effort to plot and scheme to accomplish organisation-wide improvement. Realising the collective interest (and even individuals’ self-interest) requires active orchestration.

I would be delighted to assist you structure your plotting and scheming, and realise broad-ranging improvements in performance and standing in your organisation: please contact me by return email or on 0414 383 374 and we can get started…

Warm regards,

Michael

Reference:

Chip Heath & Dan Heath (2008) Made to Stick Random House, p.182.

© Michael Carman 2019